The water in Flint is likely poisoning kids.

That’s what pediatricians in the city say, after looking at lead levels in young children before and after the city switched the source of its drinking water from the Detroit water system to the Flint River.

“My research shows that lead levels have gone up. I cannot say it’s from the water, but that’s the thing that has happened,” said Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, a pediatrician with Hurley Children’s Hospital.

Hanna-Attisha says she decided to look into blood-lead levels after researchers from Virginia Tech found elevated lead levels in tap water due to the corrosive nature of the river water.

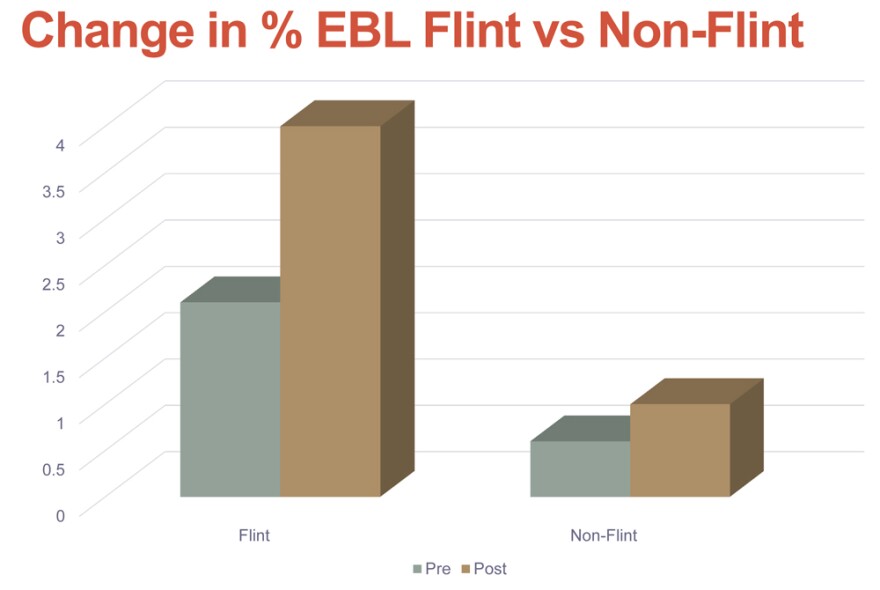

She analyzed blood test results of 1,746 children age five and younger from Flint, and 1,670 non-Flint children. Before the switch, 2.1% of Flint children had elevated blood lead levels. After the switch, that rate jumped to 4%. By comparison, the rate for non-Flint children went from .6% to 1%, which Hanna-Attisha says is statistically insignificant.

She calls the city’s response to water quality problems “inadequate,” and says precautions need to be taken immediately.

“Because the impact of not doing anything will haunt us for years to come,” says Hanna-Attisha, citing interventions like special education, lost productivity, and incarceration costs associated with high lead levels. “The cost will be astronomical in decades to come. So we cannot wait until this year or next year. We have to think five years from now, ten years from now.”

Hanna-Attisha and other physicians are urging the city to issue an advisory about how to minimize exposure to lead in the water. The county health department says it’s drafting that advisory now.

The news about the elevated lead levels did not surprise Lee Anne Walters. She found out her son had alarmingly high lead levels in April of this year.

“I kept talking to the doctors, trying to figure out why he wasn’t growing,” says Walters. “He was 27 pounds at four years old. His hair was thinning, breaking out in rashes."

Walters says her son would get a rash when he took baths. There would be a line on his body that corresponded with where the bath water ended. Above it, his skin was fine. Below it, where his skin was underwater, he’d get a rash.

“The doctors in the city gave me a hard time testing my kids,” says Walters. “I took them out the city to a dermatologist down in Brighton, who ran the test and called me personally to tell me that he did have lead poisoning and anemia from the lead poisoning, and he’s having speech problems.”

It turns out the rash was probably from a chlorine byproduct the city had to dump into the river water to kill the E. coli that had made people sick the summer before.

People knew that chemical – it’s called TTHM – was a problem. But lead wasn’t on many people’s radar until a guy named Marc Edwards came to town.

"I want them to take responsibility. I want them to quit poisoning their citizens."

Edwards is a researcher from Virginia Tech. His tests of Flint tap water found lead levels in some homes that were higher than federal regulators allow – and a lot higher than the city found in the tests it conducted. He says the river water is so corrosive it’s eating the lead from old pipes and solder.

“That’s why we are actually asking for funding to help with infrastructure,” said Flint City Administrator Natasha Henderson. “It’s not a secret that the city is very financially distressed.”

Henderson and other city officials say they’re working with state and federal regulators to get a handle on the problem.

But they’re quick to point out that the city’s own tests show it’s in compliance with the Safe Drinking Water Act.

But activists say they don’t trust how the city arrived at that conclusion, and point to the Virginia Tech results as evidence that the city has been conducting flawed testing.

“I want them to take responsibility,” says Lee Anne Walters, the mother whose son has experienced health problems since the switch. “I want them to quit poisoning their citizens.”