The Macomb County Jail has a chronic overcrowding problem. And that can make for dangerous conditions for inmates. Experts say jail overcrowding is linked to higher rates of violence, illness, and suicide.

18 people have died in the Macomb County Jail since 2012. This is one woman's story.

And perhaps the biggest factor contributing to overcrowding – which is a chronic issue for lots of jails, not just Macomb's – is the courts.

A study commissioned by the county found, among other things, that Macomb courts are sending far too many low-risk offenders to jail. The report also cited judges' tendency to set very high bail and an over-reliance on fines and fees.

Jennifer Meyers was among those tripped up by those court costs. The 37-year-old mother of three could have walked out of jail if she’d been able to pay $500 for back child support.

Instead, she died of sepsis inside the Macomb County Jail, 11 days into a 30-day sentence.

"Pay or stay"

Critics of the Macomb County courts say judges are skirting a rule meant to prevent people from getting sent to jail because they can't afford their fines. Officially, "pay or stay" sentencing has been unconstitutional for decades. The U.S. Supreme Court outlawed the practice in the 1970s.

In 2016, the Michigan Supreme Court issued a new court ruleintended to get Michigan courts to hew more closely to the rule.

But spend time in Macomb County courtrooms, and you’ll find that in at least a few of them, the spirit of pay-or-stay sentencing is alive and well.

Jennifer Meyers was booked into the Macomb County Jail for the last time on June 25, 2013. It was the 16th time since 2008.

Meyers was a heroin addict. She’d run up a long criminal record, all non-violent offenses, ranging from drug charges and retail fraud to traffic infractions.

This cycle of repeat incarceration is common for many people who enter the criminal justice system. If you’re addicted, mentally ill, or simply poor, a couple of misdemeanor crimes can snowball into probation and a pile of fines and costs that keep coming back to haunt you.

That June four years ago, Meyers was booked on four different charges. The judge ordered her to pay $500, or serve 30 days in jail.

A horrific death prompts a rule change

Civil liberties advocates say pay-or-stay sentences became a noticeable problem in Michigan around 2009, during the depths of the Great Recession. That’s when most local governments — and courts — really started to see their budgets squeezed.

But even after the recession lifted, the sentences seemed to have become a habit some judges couldn’t break. So the ACLU of Michigan began to push for a new state court rule putting strict limits on how judges can impose pay-or-stay sentences.

"You can't sentence somebody to jail just because they're poor."

“It’s unconstitutional unless the court inquires into a defendant’s ability to pay, and finds that the defendant has the ability to pay and refuses to pay,” said Michael Steinberg, legal director for the ACLU of Michigan.

And Steinberg says that refusal to pay must be entered into the court record, during a formal hearing, before sending them to jail.

“You can’t sentence somebody to jail just because they’re poor,” he said.

But for years, the ACLU made little headway getting the Michigan Supreme Court to crack down on the practice.

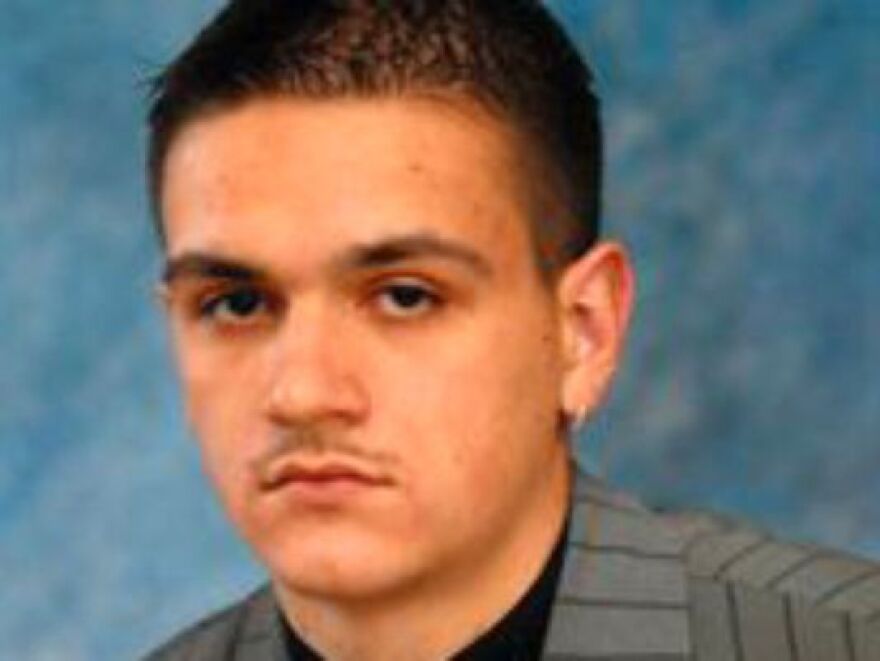

Until David Stojcevski died in the Macomb County Jail.

Stojcevski's death caused a sensation when it hit the news in 2015. That’s in part because of harrowing video footage, captured from inside his cell, that showed his protracted, excruciating death as he went through withdrawal from several prescribed medications.

Stojcevski was 32 years old. He was serving 30 days for failing to pay $772 in fines stemming from a careless driving charge.

“This was a shocking death, and the fact that he was in there for an unconstitutional sentence really caught the attention of the court,” Steinberg said.

The new, clarifying court rule took effect in September 2016.

Is the new rule being followed?

This summer, I spent some time in Macomb County’s 39th District Court in Roseville.

That’s the same court that sentenced David Stojcevski to 30 days in jail for what amounted to unpaid traffic violations.

A middle-aged man with an obvious mental impairment appeared before Judge Catherine Steenland. He was shackled and in a jumpsuit because he’d already spent 11 days in the Macomb County Jail.

He pleaded guilty to violating probation for failing to pay fines and fees over some misdemeanor charges. The man told the judge he received $700 a month in disability payments and was an Army veteran.

According to the man’s family, he has “severe mental health issues.” The Macomb County prosecutor recommended mental health treatment.

A probation officer told the judge her office had never seen the man, and said she doubted he would comply with probation.

“He’s been incarcerated 11 days, so I’d recommend credit for those 11 days served,” she said. “$820 is what he owes on our file right now. I’d recommend that paid or serve additional time, and just close out the file.”

“I don’t think that keeping him in custody without getting treatment is going to be good for him,” the man’s public defender added. “I think he needs to get into some mental health treatment. I think that’s probably the main issue as to why he’s here.”

Judge Steenland agreed with that, and there was a lot of of back-and-forth about the best way to deal with his case. It seemed he actually needed to sit in jail for about two more weeks to qualify for a mental health services referral once he was released.

Ultimately, Judge Steenland did close a number of the man’s cases and waived the remaining fees. She also gave him a 45-day jail sentence, with credit for 11 days already served, then discharged him from probation.

This was a case with few good options. But the court did not formally assess the man’s ability to pay his fines before imposing a jail sentence, as the court rule requires.

There was another very similar case that same day, involving a man already in the Macomb County jail, who also had racked up fines and fees on misdemeanor charges.

His court-appointed lawyer said of his client, who had been living in hospitals and nursing homes since his foot was amputated, “It’s a financial issue at this point, judge. He’s in and out of the hospital. I just don’t see that he can have any ability to make money and pay.”

In the end, Judge Steenland closed almost all his cases, cleared his fines, and handed him a 30-day jail sentence, with credit for time already served.

Judge Steenland could not be reached for comment this week.

The Chief Judge of 39th District Court, Marco Santia, said his court is well aware of the new pay-or-stay sentencing rules. He declined to comment on Steenland's practices, saying each judge conducts his or her own courtroom.

Any real chance for change this time?

The Macomb County Jail's overcrowding issues date back at least 15 years.

In 2005, the county commissioned a study to look into the problem and recommend solutions. Officials came up with a plan to expand and renovate the jail, but it was shelved around 2009.

In 2014, the county commissioned another study. This one took a much deeper dive into the county’s whole criminal justice system, and how it contributes to jail overcrowding.

Sheriff Anthony Wickersham says the county is already moving forward on some of the study’s recommendations. They include building a new central intake and booking facility, where defendants would be assessed based on the risk they pose before being arraigned. That should allow more low-risk defendants to be diverted out of jail.

A more radical idea put forth in the report? Getting rid of cash bail. That’s a movement that seems to be picking up steam nationwide, and Wickersham says he would support it.

“The data does show it’s safe, [and] the individuals are supervised,” he said. “So yeah, I would be in favor of something like that.”

But Wickersham is quick to add that that move, like most decisions made daily by Macomb County judges, prosecutors and other players in the justice system, is one over which he has almost no control.

This is part 2 of an ongoing series of stories about the Macomb County Jail, the justice system, and related issues.